trigger warning: discussion of sexual violence

trauma vs. genre: women of color novelists writing personally & fictively

As someone who enjoys both realistic literary fiction and speculative fiction (weird shit– science fiction, fantasy, horror, magical realism, etc), the distinction between ‘genre fiction’ and ‘serious’ writing seems to be becoming more and more arbitrary as both categories of novels continue to develop with every release of a young new author’s debut. Both speculative fiction and literary realism have a unique capacity to explore themes of women’s experiences, trauma, and socio-political commentary. In analyzing the speculative and poetic Rios de la Luz’s novella Itzá alongside the literary and dry debut novel Post-traumatic by Chantal V. Johnson, it becomes clear to me the ways that the shared thematic content within the scope of autofiction can be more dynamically interrogated when written in different genres and styles of prose. It’s not conducive to a rich textual understanding of contemporary literature to ascribe certain genres of fiction as being more or less capable of dealing with any given subject. Both books effectively convey political messaging through narrations of the authors’ personal experiences through the genre and voice they chose to embody. Beyond just both being auto-fictional accounts reclaiming traumatic life experiences, both books have incredible groundedness in space and race, as well as themes of childhood abuse and its effects. The texts explore the themes of healing from trauma as racialized women in very distinct locations in the U.S., which links these two books together despite their major differences in genre and style.

Each book brings to life and fiction the experiences of the authors’ through very specific voices of families, details of world-building with varied techniques, and tonal shifts throughout the text. Johnson and de la Luz speak at length in their interviews about these books to the extent of which these fictional novels emerge from their personal experiences with trauma, healing, and growth. With Itzá’s length being a fraction of the length of Post-traumatic, the rich and dynamic settings of the Mexican-U.S. border and New York City respectively, and characters who are– like all human beings– defined by their relationships to those in their lives, both of these authors utilize the full extent of their voices and genres to share their personal stories of healing through fiction.

Itzá intrinsically lives between reality and the spiritual, magical, and thus literarily speculative world. We follow a line of water witches living at the Mexico-U.S. border, and in “Part One,” there’s the magic of Abeulita’s neverending hair growth, Abuela’s spells on the abusers and politicians, and Marisol’s ability to physically see other people’s auras– “Sometimes, she could see a ring of color around the faces of people she interacted with. Magentas and thin ribbons of indigo meant unwavering happiness.” (34) By “Part 2,” Abuela and Abuelita have died and Marisol and Aracelli, sisters, now have to contend with their mother’s marriage to ‘Fake Father.’ In the second chapter of part two, titled “The Holy Ghost,” it becomes explicit to the reader for the first time that Marisol is being sexually abused by her step-father, and the violence of that seeps into her psyche:

“Sunday mornings, I get up earlier than everyone in the house. I steal maxi-pads from Mami’s bathroom. I line one of them on the bridge of my calcones. I tape the second maxi-pad on the outside of my underwear. I slide into white tights and add another layer with a pair of shorts. I duct tape the shorts to my belly and my legs and then put on my church dress with red roses clustered on the puffy arms and trim of the draping ensemble. This is my safety measure and my way to feel in control. This way god can’t look up my dress, and anyone who tries to grope me will only feel smooth tape and chunks of cotton.” (54)

Even as a child, Marisol weaves intent into her actions. This ritual functions nearly as a protective spell against the larger, greater forces of evil in the world. Rios de la Luz told Prism Magazine, “I went into Itzá knowing I was going to fictionalize parts of my trauma as a child with sexual abuse and emotional abuse. I knew going into it that the main character, Marisol, was going to have to go through these things and I wanted to give her the gift of healing completely by erasing the perpetrator of her abuse. I wrote Itzá as a spell.” Many chapters in Itzá read and feel like incantations and many scenes explicitly describe the ritual magic practiced by the women of this family. de la Luz intentionally wrote magic into Itzá in order to help Marisol, whom she imbued with her own experiences, as she struggles with abuse.

The aftermath of abuse, as implied by the title itself, gets explored through delusion and humor in Post-traumatic, rather than Itzá‘s witchery and magic. Johnson’s acerbically realistic literary fiction release follows a Black woman lawyer named Vivian who works at a psychiatric hospital in New York City and suffers from neuroticism, weed addiction, and an obsession with male attention antithetical to her supposed feminist philosophies. While on the train to her best friend Jane’s apartment, Vivian’s astute observations of those around her in the train car spiral: “Suddenly the man with the hat pulled out his right earbud. He touched the arm of the handrail-tapping man, to get his attention. Quickly the outlines of a predatory conspiracy formed in a corner of Vivian’s mind. They would isolate and trap her. It would be brutal.” (24) The chapter following the subway car scene, aptly titled “Jane and Mary Jane,” features these two best friends smoking weed and engaging in darkly humorous conversations about their shared histories of childhood sexual abuse. “They were high enough to be real, so Vivian could describe what happened earlier. ‘I got so paranoid on the train over here. I thought these random guys were going to, like, attack me or whatever. They were just talking, though.’ ‘I mean, they’re men. They’ve probably attacked someone.’” (33) Although nothing happened to Vivian on the train ride to Jane’s apartment, her neurotic spiral sends her into a major panic. She shifts in and out of reality due to the nature of her own delusions; the delusions rooted in the post-traumatic nature of her brain. Although the abuse she faced as a child came from people intimate to her family, nearly all of her fear of men manifests in her fear of strangers. Johnson portrays the irrationality of PTSD through Vivian’s behaviors excellently.

In a scene where Vivian takes a cab back to her apartment, she forces her way out of the moving car after convincing herself that the driver was “exaggerating his accent to she would not suspect his intent” (183) to rape and murder her. Vivian runs to the only place open so late at night, an auto body shop, and tells the mechanic “everything that had just happened to her, that the driver hadn’t made a left onto her street but instead took a detour down a darker, narrower road, that she had tried to get out of the car but the door wouldn’t open, that finally she had to crawl out, that she littered the backseat with bills, that he knew where she lived. As she spoke, the mechanic looked at her the way Vivian looked at her clients in the hospital, with pity. Then he said, ‘There’s no left turns on that street, sweetheart. They can lose their livery license if they disobey the traffic laws.’” (184) Both the anxious accumulation of phrases across commas and the racial profiling Vivian enacts on her driver exhibits the nature of her mental illness and how her traumatized brain alters her reality. Johnson doesn’t need to employ magical realism in order to portray the unreality of Vivian’s experiences; she has other techniques.

In an interview soon after Post-traumatic’s release, Johnson says: “I grew up in a household that was very violent when I was a kid. It was physically violent. It was sexually violent. It was sadistic and humiliating. From a very early age, I knew that I was hated and despised for reasons that were a mystery to me.” Post-traumatic masterfully explores the lifelong impact of childhood sex abuse and its consequences in both the main character’s personal and professional life– from her opposition to getting professional mental health treatment until the end of the novel, to the way that Vivian comes to realize in scene after scene that the mostly white people around her often perceive her as a stereotypical unhinged Black person in need of psychiatric care.

Vivian’s attitude towards psychiatry as an institution gets expressed repeatedly throughout the novel: “Working hard to dismantle that DSM,” Vivian says at a party (162), and she fantasizes explaining to a male love interest that “freedom of the mind is the basis of all other freedoms, that every person has the right to determine whether to alter their consciousness or not, and that the state should not chemically interfere with an individual’s mental state, no matter how wayward, as long as they are not a demonstrated threat to others.” (93) Through Post-traumatic, Johnson both expresses her political opinions on the nature of the world around her and fictionalizes her own experiences of being a young Black woman lawyer living with childhood sexual trauma. On a meta-narrative level, Vivian is also supposedly working on writing a novel. The autofictional nature of the text that Johnson ultimately constructs builds a hilariously compelling psychological character study in Post-traumatic.

In Itzá, the way the author inserts her political commentary throughout the text follows the same tone of poetic and somber prose, with magic and ritual underlying the statements. Scenes describing Abuela’s rage conjuring spells that force abusive men in their town to confront the consequences of their violences, pages describing the racist slurs and looks the family gets on the bus, descriptions of the inherent violence of borders and their colonialism are sprinkled across the short chapters, especially towards the beginning of the novella. Rios de la Luz’s condemnations of white supremacy are straightforward and earnest, almost serving as breaks from the deeply personal narrative in their declarative statements. Later on, as Marisol works to heal herself from her trauma, the way she describes taking back the bodily autonomy stolen from her through rituals of blood and bruises in the shower, sex with men, and boudoir photography all speak to the gender politics present within the magic of Itzá. Both Post-traumatic and Itzá have these sections of straight-up, straightforward political discourse that at first seem disjunctive against the rest of the text, but are in fact integral to the books’ construction of these characters’ development and processes of self-reflection.

As texts confronting familial trauma, gender violence, and racial issues rooted in U.S. geographies, they express the personal experiences of the authors through fiction in different shapes and styles. The genre and form of both books vary greatly. Post-traumatic reads distinctly as a realistic literary fiction novel, whereas Itzá functions as a novella with poetic style and piecemeal flashes. de la Luz describes the timeline of the text as “fragmented because when someone is healing from trauma, it’s not linear at all. There are days when you feel as though you are not even in your own body, there are days where you go into blank dazes and you can’t quite get a grasp of reality around you.” (Vol. 1 Brooklyn interview) Post-traumatic achieves something similar in the descriptions of bodily dissociation Vivian routinely experiences despite having a very linear and concrete timeline. Within the first chapter of Post-traumatic, after intervening in the potentially violent altercation with a teenage client wielding a butcher knife at the psychiatric hospital where she works, Vivian’s bodily experience in the aftermath gets described in full detail: “She realized she was shaking. Her nipples were erect. Removing her pointy-toed flats, she saw that her feet were blue and her toes had turned blue.” (6) The way she experiences her body is fundamentally distanced and immediately introduced in the text as routine for her. But instead of what de la Luz describes as not being able to “get a grasp of reality around you” as a result of trauma, Johnson characterizes Vivian’s consciousness as getting slammed with an almost hyper-reality in the aftermath of something traumatizing.

Vivian’s sensitivity to the world amidst experiencing trauma and its after effects differs from the escapism of Itzá’s sequences of “portals” that Marisol transports herself through as a mode of survival. In the “Part Two” chapter titled “Only in the soft noise,” Marisol describes her experience of being abused by “Fake Father”:

“Where do you travel when your body goes numb. You enter portal after portal and find yourself in a domesticated environment. Portal. Four stale walls with peeling paint floating onto the ground and electricity pumping into the veins of halogen lighting. You are alone in this room. This is preferable. Portal. On top of a kitchen table covered in white lace, the blood between your legs spreads. A chandelier of icicles drips into your hair and the goose bumps on your arms start to pop into ruptures of mist. Portal. Birds bounce off the walls but they never touch you. You grab at them and place the ones you catch into a pouch in your belly. Portal. The ocean in this room is on the ceiling. You reach for the water and a warmth rushes over you. You can feel your breathing normalize again, and when the room transitions into darkness, you open your eyes hoping to see the eye of a volcano.” (62)

The usage of portals functions as Marisol’s imagination protecting and distancing herself from her bodily experiences. Her placing of vividly imagined birds “into a pouch in (her) belly” speaks to the intimacy and protection she misses in the absence of Abuela and Abuelita. Marisol’s description of how “a chandelier of icicles drips into (her) hair and the goose bumps on (her) arms start to pop into ruptures of mist” embodies the transitional stage between magic and reality that de la Luz intentionally cultivates throughout the novella. The goose bumps are literal and very real, the chandelier of icicles are not. Marisol’s bodily experiences still get articulated in her coping mechanisms, and magic is her biggest coping mechanism. “Only in the soft noise” being written in the second person puts the reader in the shoes of Marisol as she experiences something horrifying and grotesque, without making her pain a fetish object. The author does not shy away from describing Marisol’s rape and sexual violation. Simply, the way that Marisol experiences the violence she survives is already at a distance. When asked about usage of the first second and third person throughout different chapters in the novella, de la Luz’s responds: “I wrote scenes this way so Marisol could distance herself from certain parts when she needed to and when she didn’t want to tell the story herself, she didn’t have to.”

As I mentioned before, Itzá’s more poetic use of language becomes somewhat broken up with straightforward political assertions that lack irony, whereas in Post-traumatic, the writing encompasses a lot of dry humor, blunt scenes, and extended intellectual monologues. Johnson consistently uses a third person point of view with a narrow focus on Vivian to highlight the neurotic distance with which she experiences her own life, and how she constantly judges herself through the eyes of others, in order to gauge perception of herself before her genuine emotions can ever show through. Even at her therapist’s office for her first appointment, after Vivian introduces her life story and the impetus behind scheduling the appointment in the first place, the therapist says, “You sound really prepared. It kind of felt like you were making a speech just now or, delivering a monologue in some play.” (283) To which Vivian laughs and responds that it’s true. As much as Vivian is neurotically put-together and almost scarily self-aware, there’s something very classic New Yorker about Vivian’s observations, and how she relates to herself and others. Very early on in the novel, she notes an interaction between a “well-meaning white woman” handing someone on the street “a half-eaten bagel” early on in the novel, smiling and thinking to herself, “Whoever said beggars can’t be choosers has never experienced the glorious recalcitrance of the New York City homeless.” (7) Another example of the dark humor that defines this novel.

In contrast, Itzá’s story roots itself in specific places through the relationships Marisol has with her family. Marisol revisits her childhood home where she was abused, in defiance of her mother: “Marisol and Araceli had not gone back to Nopales since Mami told them they were forbidden from stepping onto that property. She said there were too many demons, too many reminders of how things used to be.” (132-133) Even when Marisol gets sent to live with her Tía Lucia in Colorado as a child, Marisol’s experience with the locational difference and presence of snow de la Luz depicts shows the sharp contrast between the warm climate from where she came from, and the safety and warmth of no longer being in a house that turned dangerous due to Fake Father’s presence in it. Tía Lucia is defined by the tender aura Marisol feels from her: “She’s family and you were always told: you love your family no matter what. You know you love her because she’s the one who buys you books and sends you maps of other countries in the mail. You know you love her because when you think about her, your mind goes into a space of ease.” (69-70) Through a shift in place, Marisol’s familial obligation to intimacy becomes secondary to her own autonomy. (Also, another interesting and probably coincidental parallel to note is that both Itzá’s and Post-traumatic feature important lesbian side characters. Tía Lucia is gay, and Jane jokes to Vivian that “I like my women how I like my wine. Cold and white.”)

The mother/daughter relationship throughout both stories embody the complexity and defiance present in relationships where the person who gave birth to you and loves you also puts you in a lot of danger. In the chapter of Itzá titled “The magician,” the third person narration describes how “Marisol speaks to Mami on the phone. She keeps it brief. She doesn’t want to stir anything up. She doesn’t want to feel guilty for leaving her mami behind. She left her mami in El Paso and has never gone back. She refuses to tell Mami where she lives. She refuses questions. She won’t answer them. Even when Mami asks how she’s doing.” (127) The physical and emotional distance Marisol puts between herself and her mother and the distance of the third person voice de la Luz uses to describe their relationship indicate their necessity in Marisol’s healing process. By not allowing Mami to even know where Marisol lives now, the connection between her and an element of her traumatic past rests entirely in Marisol’s hands, thereby imbuing her with power.

In Post-traumatic, Vivian cuts off her family, consisting of a semi-distant step-father and the mother and brother who have been bothering her for the whole novel up until that point. Immediately before blocking them and changing her number, she sends a text message: “Hi everyone. It’s Vivian. I have decided that I no longer wish to communicate with any of you. The chaos and dysfunction are just too much. Please do not contact me for any reason about any issue. I wish you all the best and ask that you respect my wishes at this time.” (220) Vivian grapples with herself over this decision for the entirety of the novel up until this point, and her final conclusion parallels the enforced distance Marisol puts in place as well. It’s just that Marisol still has ties to her family and sister due to the nature of the focus in “Part One” on Abuela and Abuelita. For Post-traumatic and Vivian, Johnson expresses that she thinks that “the most daring thing (she’s) done is to criticize the nuclear family and to depict a character choosing to walk away from hers.” Difficult immediate family relationships as dynamics that still tie these characters to their traumatic pasts get resolved through the intentional distance of space and time put between each other, in both of these narratives.

These stories explore women’s survival in varied ways. Itzá is political in its poetic metaphorical voice, and what Post-traumatic lacks in poetry, it has highly ironized political moments in its place. These different internal experiences as expressed by the authors and characters of the books become fully fleshed out and embodied through the style and voice of the writing, constituting their similarities as more significant than the differences across genre categories. Post-traumatic is stylized within the character and the hyper self awareness of both her physical body and all of her thoughts on every single thing around her, whereas in Itzá, the story comes through imagery and the water witchery and portal dream sequences. Johnson’s writing in Post-traumatic is hilarious, and embodies what she has once said in an interview: “Survivor humor feels like domination to me. Abusers don’t like to be laughed at, you know.” Without making light of or reducing the severity of survivors’ experiences, both of these authors convey through their own voices and styles the power of harnessing your own story into fiction. de la Luz extends upon her use of magic in her writing: “Stories with elements of magic come out of me from a place of hope, a place of anger, a place of power… Power in the sense that as an author, the plot is in your hands, the character’s fate is in your hands. You can give them a new reality, you can give them a way of living that could only exist in their story.” Whether it be through magical spells or drily dark humor, these young women authors succeed in telling their auto-fictional accounts of trauma and healing. Literary fiction or speculative novella, their power in conquering narratives of abuse extend past the limitations of genre.

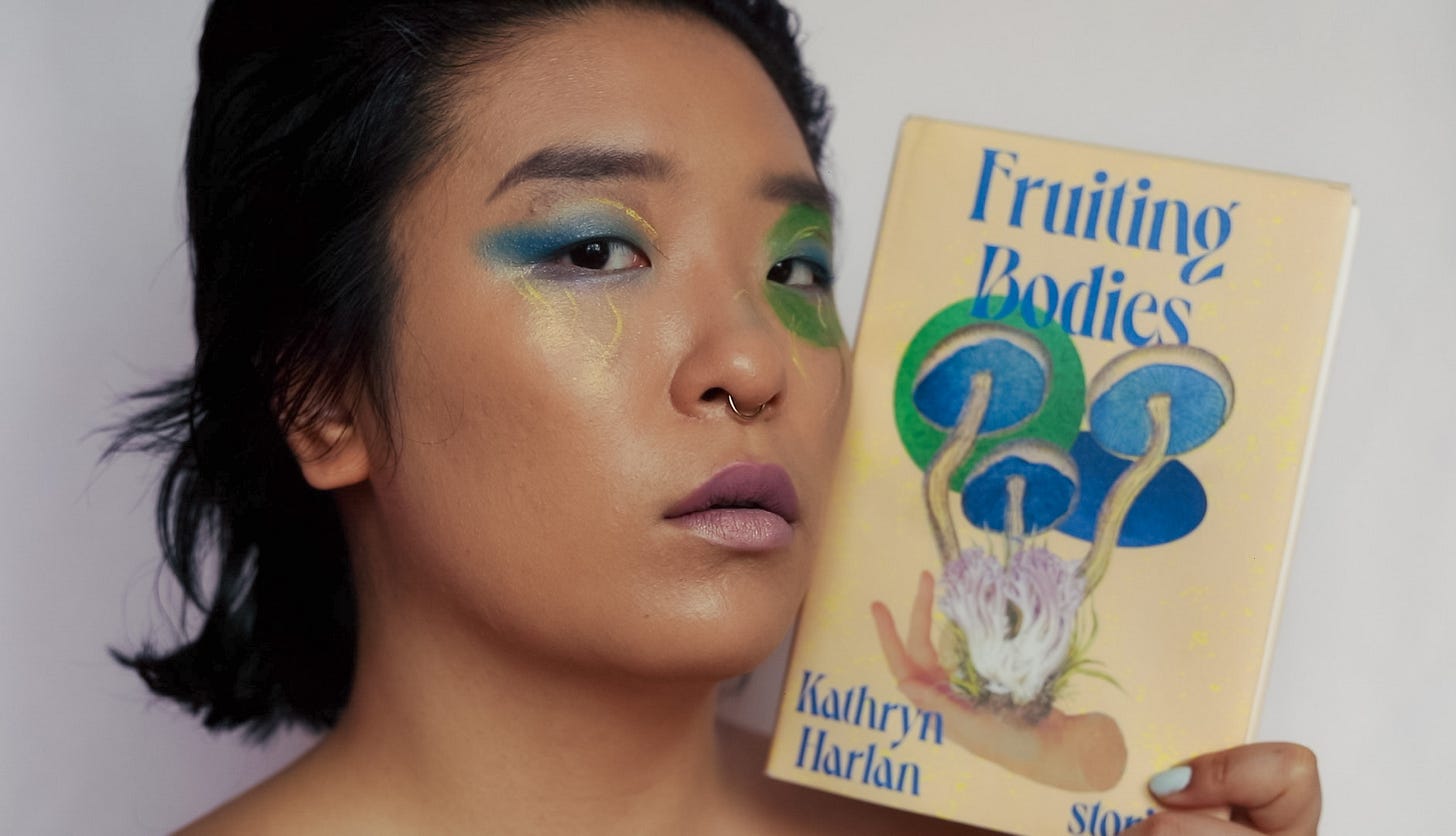

anti-capitalist (?) fairy magic economics: “Fiddler, Fool Pair” by Kathryn Harlan

Fruiting Bodies by Kathryn Harlan, a short story collection published by W.W. Norton & Company in 2022, deals with themes of feminism/queerness, the uncanny/strange, and the natural/unnatural– all within the context of speculative narratives that range from realism tinged with magic to body-horror-based fantasy. It was on my list for favorite fiction of 2022, and I’ve sung its praises on the bookternet for months. If you haven’t already heard my synopsis and pitch for this excellent magical realism short story collection yet, here goes– All of these stories are set in the ‘real world,’ a familiar contemporary landscape with characters who feel ordinary and familiar: young girls dealing with a new family member being born, a lesbian couple living on the outskirts of society, and an anthropologist writing a book. The tales become complicated as fairytale-like perspectives and circumstances start to overtake these characters’ lives and shape them. The new baby is actually a changeling, one cousin tells the other; the lesbian couple is isolated because one of the women grows mushrooms out of her body, and her partner wants to keep her secret safe; the anthropologist’s book is based on her highly guarded research of a stumbled-upon fairy casino. In understanding speculative media as it relates to the speculative financial market, I want to analyze this last short story through the framework and comparative analyses of some readings I’ve done that discuss economics and debt.

“Fiddler, Fool Pair,” follows the anthropologist, Naomi, as she attempts to understand the rules of the game in order to write her anthropological record of its existence. There are shadowy omnipresent figures around her, other players of the game, some regulars and some not, and the Magpie Queen, who seems to be the arbiter of the game’s rules. Harlan starts the story off with the following paragraph: “The game has been running under-the-hill since long before London was new and it may well continue under-the-hill long after London is gone. Even the boxy arrival of the modern calendar has failed to persuade its custodians; they do not keep to a human schedule. Like trees and cliff faces, the game under-the-hill answer to a more biological kind of time.” (101) Key to the system of debt, the trades in the gambling, and the consequences of engaging in this game is a form of time removed from human constraints and constructs. But time itself functions as a human construct for the purpose of capital, as Guy DeBord describes in section 146 of The Society of the Spectacle, “The irreversible time of production is first of all the measure of commodities. The time officially recognized throughout the world as the general time of society actually only reflects the specialized interests that constitute it, and thus is merely one particular type of time.” Harlan makes clear to the reader upon the first paragraph, the first sentence even, that “the game under-the-hill” operates on a different mechanism or standard of time, and by that measure, using a DeBordian framework, a different set of commodity forms and measurements. For Naomi, the “general time of society,” as embodied through the ‘real world’ outside of the game under-the-hill, “reflects the specialized interests that constitute it” through her anthropological journal project.

As a character, Naomi makes a spectacle of the game, which necessitates her engaging with it, and while “the stakes are too high to enjoy this game,” Naomi enjoys it on the basis of imagining “that she is the first person ever to write down the rules.” (104) Thus, the “specialized interests” that mediate the timeline of the rest of Naomi’s life are the arbiters of who can publish her ‘findings’: “For three years, the notebook in her bag has been swelling with observations on a secret people. Someday she’ll have a treatise of publishable quality. Someday, she will have enough information for coworkers, research assistants, headlines, the dependable imprint of her name on a book cover.” (106) The repetition of “someday” as well as the list of phrases separated by commas with no real conclusion or final point illustrates the way the list of accomplishments Naomi is aiming for could continue on, that her goals are simply the achievement of recognition, and that she is not interested in the ethics of spectating on, engaging with, or publicizing something she herself is keeping private– she acknowledges that “people would argue that it is selfish of her to keep this to herself. Not to tell someone with more credentials, find some research agency to take the little snow globe of the hill from her hands and crack it open.” (206) Three years of this character’s real life has been spent in the anthropological process she describes as “not first contact, the fair folk are well aware of humanity; if they wanted to be better known, they would be already. And they are dangerous.” (106) This differentiation of Naomi’s actual time and the type of time the fair folk operates under exhibits something Mark Fisher delineates in The Weird and The Eerie: “The perspective of the eerie can give us access to the forces which govern mundane reality but which are ordinarily obscured, just as it can give us access to spaces beyond mundane reality altogether.” (Fisher, 13) The space Naomi accesses of the game under-the-hill extends far beyond the pale of the laws of physics and into a magical realism that brings together fairytale and contemporary concepts such as anthropology and debt as punishment under capitalism.

Within the altered form of time that Naomi attempts to observe and engage with for her own means, “it is impossible to not make mistakes beneath the hill, where there are laws for everything; esoteric, unspoken, and compulsory.” (104) The magic of the fae as Harlan portrays has many elements of the uncanny, where the creatures and folk of the fae have human physical traits but are fundamentally non-human, and where the space in which the game takes place exists in a plane of reality accessible to humans but not determined by or existing on human terms. As Fisher explains, “We find the eerie more readily in landscapes partially emptied of the human… the eerie is fundamentally tied up with questions of agency.” (11) As a human in the fae landscape, the question of agency Naomi and the other human characters in this game under-the-hill must contend with complicates the morality of systems of debt and exchange. In this magical world underneath the ordinary reality that Naomi and the reader exist in, financial and economic exchange operates under altered systems of capitalistic mechanisms. As Annie McClanahan elaborates upon in Dead Pledges: Debt, Crisis, and Twenty-First-Century Culture, “Even a large-scale and complex event like a financial crisis is understood as no more than the consequence of aggregated individual choices. This tendency to eschew structural or macroeconomic explanations in favor of arguments about poor decision making, weak cultural values, mistaken preferences, bad taste, or excessive optimism reached its apogee with the development of behavioral economics as a subfield of microeconomics.” (25) In real world economics, the perception of individual decision making being what results in poor life outcomes or global financial crises fundamentally misunderstands the nature of capitalism. The field of economics itself, as David Graeber describes in Debt, assumes that “human beings are best viewed as self-interested actors calculating how to get the best terms possible out of any situation, the most profit or pleasure or happiness for the least sacrifice or investment– curious, considering experimental psychologists have demonstrated over and over again that these assumptions simply aren’t true.” (90) “Fiddler, Fool Pair” complicates and elaborates upon these criticisms of economists’ vision of capitalism through the miniscule underground gambling marketplace of the game.

Because the stakes are so individualized and personal to the people at the table, and “the folk are deliberate in a way Naomi finds appealing; formulaic in the same way the stories about them are formulaic,” (105) the game does not mimic large scale capitalist mechanisms of exploitation, but rather focuses on the specific dynamics of a very small magical betting game, bodily experiences as commodities and gifts, and the nature of anthropological economics. Thus, Harlan does not aim to critique capitalism as a global order through her portrayal of Naomi and the game, not because she is invested in the fictitious psychologies of microeconomics, but rather, through Naomi’s point of view, Harlan explores the metaphysical economic consequences resulting from the interpersonal relationship dynamics she constructs within this magical gambling setting. Cupbearer’s horrifyingly visible losses, Magpie’s enticement of a granted wish, and Naomi’s own interests in being under-the-hill does not replicate microeconomic understandings of finance and value, but rather explores the deeply human motives driving all economic decisions.

As an anthropological writer, Naomi’s participation in the game is secondary to her observations of it; “She bets small and nothing she is unwilling to lose. She plays close and folds early. Naomi is also a good gambler because she isn’t invested in winning.” (105) One of the other human participants in the game Naomi observes, whom she refers to as Cupbearer (sharing your real name to the fae is never a good idea!), has lost many of the things he’s bet to other players during the game. In his gambling, Cupbearer has lost everything from “reading, writing, his voice and tongue on separate occasions, every poem he ever learned, dancing” to “pleasure in food and pleasure in sex.” Also, “his mouth and nose are blank cuts in his face.” (107) Harlan draws out Cupbearer as a deeply unsettling figure, a human who has lost much of himself to the fairytale game under-the-hill. “Naomi has no way of knowing what first brought him under-the-hill, if he came seeking a favor from the folk or just out of reckless curiosity. If he ever had a purpose here, Naomi can’t imagine it’s survived his ever-deepening spiral of sunk cost. Every night she’s seen him play, he’s gone full-tilt. Sometimes he wins a piece of himself back from a returning player, but never enough to justify the risk and usually less than he loses. If he ever won the favor, though, he could ask Magpie to restore him to himself, and maybe this is just enough hope to keep him from finding his better judgment. Or maybe that too was bet and lost before Naomi even encountered him.” (107) The fact that non-material things such as one’s “better judgment” and memories of experiences, as well as body parts, can be won and lost– “(Naomi) considers it wise to lose something of her own on occasion, not to seem competent enough to game the system, though she wonders if she might be, given the chance. Of her own things, Naomi has lost her left pinkie finger, the memories of her first kiss and of her sister’s birth. The color red, a ring her father left her, and the taste of blackberries with cream. The game advantages new players. It’s possible to bet small things until you run out of small things. Naomi does miss blackberries.” (110) – provides an interesting economic reality situated in the fantastical, but related to and extrapolated from the very real commodification and exploitation of human experiences and bodies under global capitalism, within a fairytale framework: “She once saw a pregnant woman gamble and lose her firstborn child.” (108) This common fairy tale motif understood as an element of microeconomic exchange illustrates “the economic and historical relationship between domestic debt and the speculative market in debt backed by that debt—and, by extension, the conceptual relationship between the individual and the whole, between the micro and the macroeconomic.” (McClanahan, 24) The debt that is owed microcosmically and micro-economically ties the human players forever to this game. Parallel to the schemes of finance capital that gamble with people’s debt in our reality of late capitalism, any observation and participation result in inevitable losses. Naomi has lost her ability to taste a dessert, and a human she has observed anthropologically has lost her unborn child, all as consequences of playing a game run by fairies under the hill.

However, the fact that players just starting out have the advantage of being able to bet small things without losing as much of themselves reveals that the game cannot exactly be a microcosm of how capitalism works. In that way, “Fiddler, Fool Pair” does not have the simplistic moral arc of actual fairy tales. Unlike socialist fairy tale collections such as The Castle of Truth and Other Stories by Hermynia Zur Mühlen, Harlan constructs both the fantasy world’s gambling system and the characters as having much more complicated systems of morality than a simple fable delineating how capitalism is bad through a fairies’ game. Because ultimately, Naomi’s participation in the game is about anthropological observation more so than accruing capital, or the magical equivalent of capital, which “is at every level an eerie entity: conjured out of nothing, capital nevertheless exerts more influence than any allegedly substantial entity.” (Fisher, 11) This is doubly true for the items and experiences on the betting table of the fairytale game Naomi is engaging in, because none of the exchanges are substantial in a large scale capitalistic sense. “Risk management is key to Naomi’s research under-the-hill. The game’s stakes escalate with each round of bets– the more she plays, the more and worse she may have to forfeit. And since the prizes are incidental to Naomi’s purpose here, winning big carries dangers of its own. Most of the human players seem to be drawn here by Magpie’s promised favor, that personal miracle to salve whatever ache originally set them wandering through the world’s strange, dark places.” (109) Naomi sets herself apart from the other human players, who she determines are there to try to win the game rather than understand it.

All of the human players are drawn to this “eery entity,” this high risk game where you can lose your body and memory but can win a granted wish from Magpie. And while it wasn’t her goal, as the story progresses, Naomi gets dealt a winning hand and undergoes experiences that destabilize microeconomic understandings of capitalism and relationships as they relate to embodied experiences and human identity. As Graeber describes in Debt: “In cases of barter or commercial exchange, when both parties to the transaction are only interested in the value of goods being transacted, they may well– as economists insist they should– try to seek the maximum material advantage. On the other hand, as anthropologists have long pointed out, when the exchange is of gifts, that is, the objects passing back and forth are mainly considered interesting in how they reflect on and rearrange relations between the people carrying out the transaction, then insofar as competition enters in, it is likely to work precisely the other way around.” (103) Naomi’s position as an anthropologist and spectator is intrinsic to the nature of this narrative, because otherwise, a microeconomic behavioral psychology based understanding of navigating the landscape of this game would produce a far less interesting short story. Unlike the capitalism of Naomi and the reader’s real world, the game does not pretend to be fair or impartial. “The system here is imprecise, the value of a bet determined partially by how interesting the item is to the others at the table but also by what it means to the player to lose it. The most material things, the most replaceable, always fall early.” (110) In this way, relationships involving the commodity form as economists understand it cannot be applied to this story’s framework, because what is being bet functions more as gifts than economic commodity exchange. “Fiddler, Fool Pair” takes no interest in critiquing unfair economic exchanges as a consequence of capitalist relations, portraying the gifting/betting/debt mechanisms of the magical game as an anti-capitalist alternative, or moralizing gambling as a societal ill resulting from capitalist exploitation. Rather, the character arc of Naomi as an anthropologist reveals the fallacy of behavioral microeconomic decision making applications when it comes to exchanges involving human experiences and relationships, which is all of them. Spoilers ahead for the rest of the story, so go read this short story collection for yourself if you haven’t already!

Something Naomi reminds herself as she is playing the game is: “Never forget that your presence will influence your subject. Never forget that your subject is responding to you.” (124) Even when she is self-aware about this regard, when Magpie reveals that she knows that Naomi has been recording information in order to publish material, Naomi understands that “she can never return. Not now that it is all out in the open, her research butchered on the table, and the folk may seek novel ways of toying with her. Three years of study, and she still can’t predict them with any certainty.” (134) Regardless of any awareness Naomi has gathered over the years, she ultimately makes the decision to forgo her own research project when she wins the wish Magpie can grant her, and “points to Cupbearer, his empty, ugly face, his closed, single eye… ‘Give everything back to him.’” (134) Through the magical mechanisms of time and experience mediated through the magical realism of the fae, Naomi has experienced Cupbearer’s lover’s memories of them together through the bets she has won, and even though everything in the narrative leading up to this moment points to her own interests and self regard as being prioritized above all else, she gives up all of her research and goals in order to grant life back to people she has minimal relationship with. “This day was a victory of sorts; it will be a little while before she runs out of things to write about… She has committed either an unforgivable waste or the first really good deed of her life.” (135) Naomi is still weighing the consequences of her actions in the aftermath of her decision, and her selfishness has not gone away within her characterization, but ultimately, the anthropological understanding of the gift economy supersedes the financial and economic understanding of the debt economy. When the person she saves turns to her and says, “‘I owe you a debt, Lady… Thank you. I– I don’t even know how to. I was so–’ Naomi does not say, Don’t go back. This is not how to thank her; she does not want his thanks. She wants to ask him if he thinks she made the right decision, but she has no reason to trust his answer.” (136)

Morally and intellectually, Naomi feels the weight of the contradiction she just lived out, but the life that she saved at the expense of her own research and purposes speaks to how when it comes to exchange and debt, “there is almost always felt to be something extraordinary about saving a life… throw(ing) all everyday means of moral calculation askew.” (Graeber, 93) By the end of the story, Naomi “does not want his thanks.” She had the onus of the decision making resting on her shoulders because Magpie’s power had been redistributed to be determined by Naomi’s desires. As Graeber notes, “One could judge how egalitarian a society really was by… whether those ostensibly in positions of authority are merely conduits for redistribution, or able to use their positions to accumulate riches.” (113) But because the game under-the-hill is not interested in egalitarianism nor does is necessarily constitute a society of its own, but is a space mediated by a different and altered form of time and logic, Magpie’s hard won “redistribution” brings into question complicated approaches to the morality of economic exchange, especially because the consequences of such exchange are so tied to the bodily experiences and livelihoods of the participants. Graeber continues: “In exchange, the objects being traded are seen as equivalent. Therefore, by implication, so are the people: at least, at the moment when gift is met with counter-gift, or money changes hands; when there is no further debt or obligation and each of the two parties is equally free to walk away. This in turn implies autonomy.” (108) By the end of “Fiddler, Fool Pair,” Naomi and the two men she has helped save from the game under the hill are the “equally free to walk away,” but they have both suffered immense losses, of time, their relationships, the work they’ve put in, pieces of themselves, and precious experiences for the purpose of being able to experience these gifts and counter-gifts of the gambling table. The moral of this story then, cannot be simplified to an anti-gambling narrative, or the inherent amorality of spectating as an anthropologist, nor is it a microcosmic representation of global capitalist exploitation, but seeks to question constructions of debt and the gift economy within a complicated moral framework of differing interests and ambitions of the characters.

thank you for reading. <3